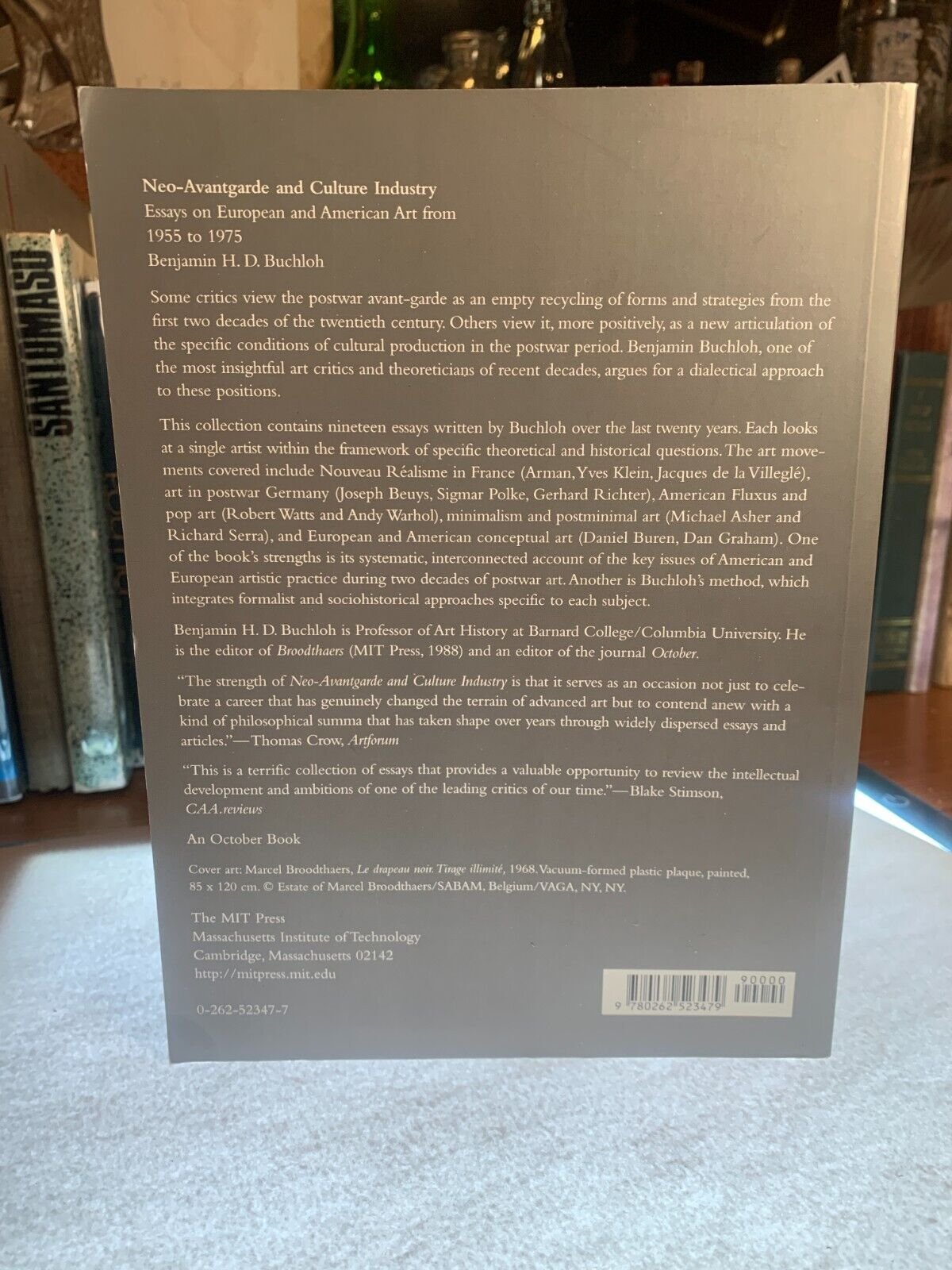

Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry : Essays on Art. 2003, MIT Press

Contemporary visual art is often slick and narcissistic, and bears a disturbing resemblance to sophisticated advertising and music videos. Ugo Rondinone’s coolly smoldering, slow-motion videos might well be promoting a new line of perfume, and Pipilotti Rist’s hallucinatory work, which was featured on an immense screen hovering over Times Square, evokes fashion shoots and designer clothes for sassy, hipster girls. The emotionally distant, grotesquely erotic nudes by painters like Lisa Yuskavage and John Currin, rather than troubling the representation of the female figure, weirdly affirm and take pleasure in its status as a fetishized commodity. The art of Rondinone, Rist, Yuskavage, and Currin, and one might add Matthew Barney’s wildly operatic films as well, has a fin de siècle decadence which eschews the politics in favor of luxuriantly over-refined and perhaps cynical aestheticism. In sharp contrast, the Neo-Avantgarde artists of the 1960s and ’70s mounted an analytical critique of the nature of art making and of art objects in an increasingly commodified society, and also of the compromising institutional context in which cutting-edge art is exhibited. Benjamin Buchloh’s weighty, 600-page tome, Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, centrally focuses on Neo-Avantgarde artists like Michael Asher, Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren, James Coleman, Dan Graham, Hans Haacke, and David Lamelas, artists whose work is driven by an aesthetic and institutional critique, and yet which resists the total reduction of art to linguistic propositions promoted by conceptual artists such as Joseph Kosuth.

From The Brooklyn Rail whose great review of the book is worth the read.

Contemporary visual art is often slick and narcissistic, and bears a disturbing resemblance to sophisticated advertising and music videos. Ugo Rondinone’s coolly smoldering, slow-motion videos might well be promoting a new line of perfume, and Pipilotti Rist’s hallucinatory work, which was featured on an immense screen hovering over Times Square, evokes fashion shoots and designer clothes for sassy, hipster girls. The emotionally distant, grotesquely erotic nudes by painters like Lisa Yuskavage and John Currin, rather than troubling the representation of the female figure, weirdly affirm and take pleasure in its status as a fetishized commodity. The art of Rondinone, Rist, Yuskavage, and Currin, and one might add Matthew Barney’s wildly operatic films as well, has a fin de siècle decadence which eschews the politics in favor of luxuriantly over-refined and perhaps cynical aestheticism. In sharp contrast, the Neo-Avantgarde artists of the 1960s and ’70s mounted an analytical critique of the nature of art making and of art objects in an increasingly commodified society, and also of the compromising institutional context in which cutting-edge art is exhibited. Benjamin Buchloh’s weighty, 600-page tome, Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, centrally focuses on Neo-Avantgarde artists like Michael Asher, Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren, James Coleman, Dan Graham, Hans Haacke, and David Lamelas, artists whose work is driven by an aesthetic and institutional critique, and yet which resists the total reduction of art to linguistic propositions promoted by conceptual artists such as Joseph Kosuth.

From The Brooklyn Rail whose great review of the book is worth the read.

Contemporary visual art is often slick and narcissistic, and bears a disturbing resemblance to sophisticated advertising and music videos. Ugo Rondinone’s coolly smoldering, slow-motion videos might well be promoting a new line of perfume, and Pipilotti Rist’s hallucinatory work, which was featured on an immense screen hovering over Times Square, evokes fashion shoots and designer clothes for sassy, hipster girls. The emotionally distant, grotesquely erotic nudes by painters like Lisa Yuskavage and John Currin, rather than troubling the representation of the female figure, weirdly affirm and take pleasure in its status as a fetishized commodity. The art of Rondinone, Rist, Yuskavage, and Currin, and one might add Matthew Barney’s wildly operatic films as well, has a fin de siècle decadence which eschews the politics in favor of luxuriantly over-refined and perhaps cynical aestheticism. In sharp contrast, the Neo-Avantgarde artists of the 1960s and ’70s mounted an analytical critique of the nature of art making and of art objects in an increasingly commodified society, and also of the compromising institutional context in which cutting-edge art is exhibited. Benjamin Buchloh’s weighty, 600-page tome, Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, centrally focuses on Neo-Avantgarde artists like Michael Asher, Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren, James Coleman, Dan Graham, Hans Haacke, and David Lamelas, artists whose work is driven by an aesthetic and institutional critique, and yet which resists the total reduction of art to linguistic propositions promoted by conceptual artists such as Joseph Kosuth.

From The Brooklyn Rail whose great review of the book is worth the read.